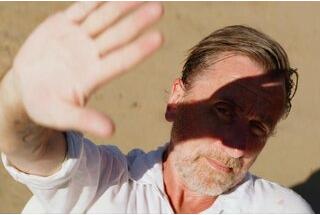

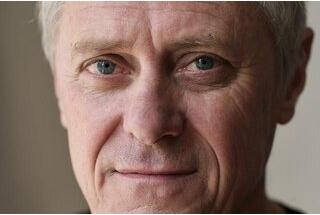

Yves Cape, AFC, and his collaboration with director Michel Franco - Part 1

By Caroline Champetier, AFCTHE MEETING

Caroline Champetier: I really liked what you said about Memory on the AFC website, where you describe a real change in the way you work, no doubt due to the possibility of having lighter lighting tools and more sensitive sensors... I have the feeling that it’s also Michel Franco and his directing proposals that have brought you to this place. I wanted to know if you could talk again about Sundown, which is your fourth film with him, and what you said about Memory, that way of reacting on the spot, despite having prepared a lot in advance.

Yves Cape : What’s special about working with Michel Franco is that we’re not at all from the same generation. He’s someone who studied classical cinema, who’s been a camera assistant and a bit of a cinematographer, so he’s familiar with film, but he was born with digital technology. So his approach is totally different from mine. When we made our first film together, Chronic, I came with my old 35mm film reflexes, even though I’d already shot digital and adapted digital to my 35mm habits, and not the other way round.

I found myself in situations where it was normal for Michel to shoot rehearsals, because there were no longer any questions of quantity. The flexibility of the tool also meant that we could shoot at night in a street, and suddenly prefer the scene to take place not in the street, but in the apartment on the second floor.

A preparation that used to be heavy, I realized that I could make it lighter by working differently with the tools, the light, the camera and the lenses. As soon as he’s shot one or two takes, the card goes to the editor on set and he puts it in the film’s timeline. So Michel moves very, very fast, whereas I was still used to a slower pace. I was really driven by him, in other words, pushed by him to get rid of a whole cumbersome system.

On Chronic, Tim Roth and I often talked about it, because even for actors it’s quite disturbing. Michel is capable of saying to himself, while he’s shooting a shot, "This isn’t the shot I want.

It’s very destabilizing for an actor, because he’s telling him: "Don’t worry, go ahead, we don’t know how yet, but we’ll do it differently...". On the other hand, he wants to see it, because it allows him to bounce back and explain why he doesn’t like it. For Tim and me, it was really destabilizing, because we’re used to pushing things to the limit and wearing them out. Michel realizes that it’s not what he wants, whether it’s the acting, the camera movement or position, the lighting, or whatever he’s directing.

Tim and I were, at times, quite overwhelmed and disturbed by this speed.

CONTINUITY AND LIGHTNESS

CC: But does that mean he shoots in continuity?

YC: Yes, he shoots in perfect chronology. Michel delegates a lot of things to me, including giving total responsibility for the work plan to the assistant director and me. I only go to see him when I have doubts, when I say to myself, that’s a pity, we shouldn’t shoot that in the chronology, because it would allow us to do this or that, but he has great confidence in us. The assistant director changes, and I haven’t changed for six films. It’s the same for costumes and sets, he sends me to the front to talk to them. Obviously, I give Michel feedback to make sure I don’t make any mistakes. The idea is obviously not to decide for him, but he lets me take on that responsibility.

The chronology on Memory we deconstructed a little with Lisa Man, the assistant director. We had three main sets that recurred in the film, and for financial reasons, because it was easier to rent sets one after the other, we made blocks. There was only one set where we came back twice, because in the original script, that was where the final scene of the film was. So we started shooting certain scenes discontinuously for two or three days, and Michel said to us: "It’s not possible, I can’t do it, it’s not your fault, but I can’t do it like that, I have to move forward in the chronology". It’s his way of working with the script and the actors that imposes this, he waits for the actors to seize the scenes. There are many working versions of the script, but once there’s the shooting version, even if changes may appear because the sets impose something, he doesn’t modify the script any more, because for him, that’s not what’s important. What’s important is what’s written in the scene, whether it takes place in the kitchen or the living room, who cares, but on the other hand, he wants to see how the actors take hold of the scene. He’s not at all "Show me, I’ll tell you what I think", he gives a lot of indications beforehand, where he wants the actors to sit, their movements, but he checks with them that it’s working. So there’s a great deal of freedom, and at the same time strict instructions.

On the other hand, Michel is very attached to making as few shots as possible, because he thinks there’s always a way to find a single axis for a scene. All this demands a great deal of flexibility, which is why my system on Michel Franco’s films has become so much simpler. If I were heavier, I wouldn’t have the time to move all this equipment around.

A good example is lighting through windows, which we like to do; even if it’s on the ground floor, where it’s perfectly possible to put a tripod and a light source, with Michel it’s complicated because we might be shooting the scene inside, or on the stoop, or at the front door, so I’d set up things that wouldn’t be of any use to me. As a matter of fact, on Chronic, which was our first film together, after a week I sent back some electrical equipment because I realized I’d never use it. I had taken, as I always do, six SkyPanels, a source I use a lot, and I figured two would be enough. What’s nice about it is that there’s a kind of playfulness in it, i.e. it’s not dogma, we have dogmas, but at the same time we’re delighted when we transgress them, because it makes us laugh that we give ourselves rules and that our rules don’t necessarily work. On the other hand, we really like this lightness, a scene that’s in the kitchen, we can say to ourselves that it’s better in the bedroom and better at night, so we have to use curtains, so I anticipate all that, I always ask for curtains, because I know that a scene planned for daytime could be done at night, and because I don’t want a black window, I need curtains.

On Chronic, I had a hard time of it, because things went so fast. Michel shoots almost all his films in 24 days and a day of reshoot on the work plan, five weeks, that’s American rhythms, 12 hours of work, in Mexico it’s the same thing. I often live with Michel, so our conversations continue after the shoot. On Chronic I didn’t live with him, and it’s true that I had moments not of panic, but of doubt and anxiety, saying to myself: "Am I going fast enough? Is my system too cumbersome? If I tell him I need 20 minutes to put a plan in place, he accepts. He’s never said to me: "No, I’ll be there in 10 minutes".

REHEARSAL

YC : Michel always has me present at the first rehearsal, where I don’t interfere at all but watch. We get into the room, we read the script, which we’ve already read 50 times, and we both move around, saying, "Here’s me sitting here, here’s one of the characters, is he going to get up, do we want to see him leave? Once the actors arrive for this first rehearsal, before going to make-up, Michel explains the scene to them. If it’s more complicated, he tries things out with them, until we find the scene, then they go to make-up and we start shooting. That’s where I can’t lose any time because of the chronology: if we’re in the kitchen and we’re going to do the next scene in the bedroom, it’s interesting for the actors to follow on almost directly. So I realized that it’s also a pleasure for me to see the actors seize the scene. I know that for them, two hours of lighting installation breaks their momentum. I’ve come to love this system, which Michel and I have perfected together, film after film.

On Memory, it was a new team, so we had a meeting and had to explain how Michel wanted to shoot to the production team, the control room and the trainees, so that everyone understood. Michel made it clear to them that it was a kind of co-direction between him and me, in the sense that a whole series of questions were not to be put to him, but were to be directed to me. One of the assistant directors had taken notes at this meeting, and we turned them into a document that I really like.

For example, the eternal question, where do we put the trucks? It’s impossible to answer this question easily, because we have to be able to move easily and quickly everywhere! So the trucks aren’t in the immediate vicinity of the set. It’s complicated, because I know that the equipment will take longer to get there, but that’s just the way it is, there are rules, and we prefer to warn them before the shoot, saying that the rules are a bit strict, a bit strange.

Michel doesn’t want anyone on the set except the necessary people, i.e. if it’s possible, he doesn’t want the make-up artist or the hairdresser or the best boy or the assistants, but he accepts that they be behind the screens. In fact, we try to limit the number of screens, but the staff are entitled to a screen, not big screens, but small ones, but the editing is there for them too, and he tells them: "You can go and see the editing whenever you like". He also allows everyone except the actors to watch the rushes. At scene time, if they need to look at their work, there’s this little screen, and he tells them: "Above all, if you have a problem with make-up or anything, ask Yves to come and look through the eyepiece of the camera", and I have no problem with that.

As usual, the rules seem strict at first, but once people understand the system, they get used to it. It’s always better to have a gaffer behind you so that he can watch the scene, follow a take, and if he sees that it’s going well, he goes behind the monitor; if it’s more complicated, he stays.

In fact, it’s quite pleasant because the people who take part in the shoot internalize these rules and realize that they have a stake in the system. The last film we shot in San Francisco, called Dreams, the first week I felt the American crew were really unsettled. I said to them: "Be careful, it’s going to be like this for five weeks, if you’re unhappy, you’ll have to leave, because there’s no reason for you to be unhappy, on the other hand I think it could be interesting for you because there’s a way of participating, but there are rules for participating". In fact, it lasted two days! The following week, the gaffer, Clay Kerri, became an extraordinary partner because he understood the mechanics and why we wanted to do it. It’s confusing for the technical crews, when all of a sudden we tell them: "We’re going to shoot in this axis", and then just afterwards Michel and I say: "No, we’re not interested, we’d rather shoot in the other axis", they think we’re a bit of a joke, but at the same time, once they’ve understood that it’s because the blocking isn’t working, they’re won over.

For all these reasons, I had to lighten my system! On Sundown, Tim Roth’s entire room in the second hotel was pre-lit because we often go back there. It’s a light pre-light: there are 12 meters of Boas in three 4-meter rows on the ceiling to create penumbras or raise the daylight level if necessary. At Memory, too, all the rooms were pre-lit, but we didn’t have enough equipment for all the rooms, so we had to modify them according to the work plan. For the lighting engineer, Jay Warrior, it’s a real installation challenge. Contrary to what people often think, it’s not at all pure natural light, where we don’t use any spotlights, but we always try to keep things as simple as possible. I really want to simplify my life in terms of lighting, and the day-to-day work for the crew, so that I can devote as much time as possible to blocking.

BRAINSTORMING WITH THE GAFFER

CC: It’s a lot of thinking beforehand about openings, doors, windows or sources of light, a way of anticipating various situations - day, night, evening, twilight?

YC: That’s exactly it. I put myself in a room with the members of the technical team, and we plan the different situations of day, night, twilight, how are we going to do it? An example, as is often the case in a certain type of popular hotel, the floors have a color, either paint or light, in the second hotel, on Sundown, which by the way isn’t the happiest thing we’ve done, talking about the night on the terrace, we said to ourselves: "Each floor has a color, what color?". The top floor we were shooting on was unoccupied, so we could choose the color.

CC: I think red, red isn’t exactly a red, but I really like the idea of monochrome.

YC: It really came about through discussions with the gaffer, Natcho Sanchez - whom the production company introduced me to, and with whom I’ve made three films now - and we put ourselves in all kinds of situations. We said to each other: "Hey, when we’re on the terrace at night, what are we going to do? There was a hotel a bit further on, so we thought we could maybe have a SkyPanel down there to give a bit of detail on the facade, but on this side it’s much too far away, so we’re not interested, we’ll see if there are any light points, and what about the terrace? We’ll see if there are any points of light, and what about the terrace? Do we bring in light from inside, but this interior is quite dim, there are only two small lamps above the bed, so there’s no reason for the light to shine so far.

So we decided on white Asteras, and then the lighting designer suggested, "Let’s do it like the other floors. At first I said no, but the next day I said to him, "You’re right, that’s a good idea, but what color?" So we did it in pink, then in color-grading, I found the pink unconvincing, so we changed it to red. All this also involved a lot of choices for us, which is fun. For example, in the night scenes where they’re making love in this bedroom, I said to myself, they’re making love in the half-light, but the light from the terrace is still there. Should I use pink backlighting, or red backlighting, or do I like that?

CC: There are moments when you bring back the colored backlight when he’s sitting on that terrace, I liked that, anyway they’re arbitrary proposals, but at the same time they can say something about what the characters are like.

YC: Well, that’s the other thing that’s important, because with my lighting technician I do this technical reading of the locations, so we’ll see the different lighting effects in all the sets, in the cars too, well all the sets, then secondly there’s the scenario again, so the character, his solitude, the guy who’s trying to escape from something we don’t understand, who’s dying, but we don’t really know what... I often say to myself that the frame is going to help us translate that, him all alone in that room, wide shots to mark his solitude. Of course, the lighting obviously plays a part, but it’s really a setting that I reserve for the moment of shooting, because I can never know exactly what the actor is going to do and how he’s going to take over the scene. As Michel leaves them a lot of possibilities, sometimes with proposals that he rejects, but often with a wide margin of freedom.

Tim Roth is an actor Michel adores, he has a lot of suggestions and at the same time understands the script deeply, he doesn’t have suggestions that go off in all directions but he always has them. Tim is perfectly capable of sitting with his back to a scene where he knows the camera will film him from behind, thinking it’s better that way, and if he sees the camera moving, he says to me: "No, stay there, that’s where it’s good, and I’ll turn around at some point and find a way for you to see my face". So it’s more at this point that we have these discussions with the gaffer, but we manage to have them precisely because we’re very simple and very prepared, we don’t have to set a lot of things in motion, it’s just turning on a lamp because we say to ourselves: "Well, he’s got the lamp on in his room or, on the contrary, he’s staying in semi-darkness", so we have our system on the ceiling which allows us to create this semi-darkness and our equipment close to the outside to light from the outside if we want.

That’s what Michel taught me, and obviously it doesn’t work with every film, because you need to have a lot of trust between us, because he could get me into a lot of trouble, but he doesn’t, and especially if he does so inadvertently because he doesn’t understand, I can tell him and he’ll say, "Okay, I understand, we’re not going to do it like that, we’ll do the shot tomorrow so you have time to prepare". So this chronology obviously helps us, because even for me it’s fantastic to move forward knowing what I’ve done just before. We’re always talking about actors, for whom shooting in chronology is pleasant, but for a cinematographer, it’s fantastic.

FRAMING AND FOCAL LENGTHS

CC: What you’ve just said leads us to talk about the frame. Your optics panel is a series of classic lenses ranging from 18 to 150, how many lenses do you work with? It reminds me of Beauvois, who knows perfectly well the axis in which he wants to look at the scene. Is he just as sure of the value of the shot, i.e. the focal length?

YC: There are two things that come into play: Sundown is shot anamorphically, so for budgetary reasons, in Mexico, we had the only series available from our rental company CTT, anamorphic Cooke lenses (25/32/40/50/75). I tried them out and realized that the 75mm had a very noticeable blurring problem at the top and bottom of the image, which can be annoying for close-ups, so I cropped to avoid this blurring entering the eyes. Overall, it’s a 40mm lens, which is our reference focal length when we’re not using anamorphic lenses. So it’s a very important focal length for us.

For wide shots, as Michel hates optical distortions because they bring in things he considers to be a point of view that isn’t his own, he finds that it’s not his vision, so we avoid very short focal lengths and have had to go to 25mm quite rarely. The wide shots in the bedroom, when we’re at the very back of the room, fixed camera, they’re at 32mm, I can’t remember exactly. After that, the question arose in the other direction, i.e., all of a sudden for Michel, 100mm or 150mm would give a long focal length effect, and again it was an effect he didn’t want, so we didn’t use them. So, overall, we shot the film at 75mm and 32mm.

When we work with Summilux lenses, our focal length in 1.85 format, it’s 40mm pretty much all the time, so when we have to do a wide shot that we can’t do at 40, we go to 35 or 25.

CC: Was Sundown your first anamorphic film?

YC: Yes, our first anamorphic film. We’d done Chronic, Les Filles d’Avril and New Order in 1.85, and Michel wanted to make a change. Then there was this reference to L’Etranger, by Camus, this lonely person on a beach being grilled in the sun, this solitude...

In preparation, Michel had said to me: "Why not try 2.40 once? So I suggested: "As long as we’re doing 2.40, let’s go anamorphic".

I don’t think there are any rules that apply better to one film and less well to another, but it’s always an aesthetic choice, and you conform to that. But, for example, when you’re in the back of the room and you have to pan around the drawer, you can’t use a short focal length because that would cause distortions that Michel wouldn’t tolerate.

CC: When we’re in the room at the second hotel?

YC: Yes, in his second room, the camera is right at the back of the room, and there’s a shot where the character comes in and hides his phone in the drawer of the bedside table. There, we can’t use a short focal length because panning would cause too many distortions, too many line movements that would disturb Michel, so it imposes a choice of shot, and we like that, these constraints. In this case, we decide to pan around and get a close-up when we arrive at the drawer with a nice cut of his entrance at the door, which again has to be the equivalent of a 40mm, so in anamorphic, the 75 or 50. Our rule is no effect!

CC: Yes, the question of neutrality seems important!

YC: The choice of focal length also implies the distance at which we film, and that’s the most important thing in my opinion, more than the aesthetic aspect. As a general rule, we’re always with the characters, we like to be close to them, it’s their story we’re telling, so Michel wants to have a normal physical distance, between them and between the camera, so obviously that imposes something because if we say to ourselves that it’s the physical distance between two people that’s important, the focal length adapts to that and not the other way round. In a way, we fall back on the things we like, i.e. 40mm, so in anamorphic, 75 or 50. But that’s what I like about Michel, is that he leaves me a lot of room to maneuver, the only thing is that he has a very good eye and as soon as he sees on his monitor or in the camera that there’s something wrong, he tells me: "There’s something wrong, I don’t know what but there’s something wrong". So I try to think about what’s wrong with it, and sometimes it’s just that I haven’t put the right focus on it.

CC: It can also be a question of proximity, when you have the possibility of moving closer or further away.

YC: Exactly, it’s true that when it comes to lighting the actors, we know that it’s easier to have the camera further away from them, so he takes me back on the fly, i.e. he tells me: "No, we have to get closer, it’s physical", if the two characters are talking to each other and we’re with them, we don’t go into the next room to film them, even if it’s more beautiful!

CC: Speaking of which, there’s a tracking shot in the film, a track on the beach behind a first row of people sitting on chairs or sitting on the sand facing the sea. How did you decide on this tracking shot?

YC: Once the character has arrived at this second hotel, which is in a different part of town, a new film begins. We had the first part with his family in a luxury hotel, the announcement of his mother’s death and then the airport, where he claims to have forgotten his passport. From there, the second part begins, he asks the cab driver not to go back to the first hotel, he takes him elsewhere, he takes a room in a popular hotel by the beach and then goes out on the beach.

With this other film underway, his own story begins. For us, there was one very important thing - Michel is extremely dogmatic about these kinds of details - this beach in Acalpulco was chosen because Michel had spent his childhood there, on the one hand, and above all because the events we’re describing, the shooting that takes place, really took place on this beach, which is known for that. There are always stories of smuggling and murder, it’s an extremely popular beach unlike other beaches in Acapulco, and it seemed important to us to enclose within a perimeter his hotel room, the beach, the restaurant where he goes, well, this beach umbrella where he’s always going to tan himself, he meets the woman elsewhere in a store quite close by, and this geography was very important to us: the hotel, the girl’s store, the beach and the area of his umbrella. The central part of the film takes place there, right up to the moment when he has to leave the beach. This geography was a real subject, and we wanted to present this rather special, very popular beach where there are lots of people and restaurants all along the way. The travelling shot came quite naturally when we said to ourselves: what we have to show is the sea, the beach with all these incredible people and Tim anachronistic in this setting who don’t really know where to go and end up stranded in one of the beach bars.

CC: How many meters is this track?

YC: It must be about twenty meters long, maybe 30. I didn’t have that kind of freedom before, and above all I perhaps had the dogmas of our old school, which I find a little outdated. I think that directors are starting to take advantage of what digital technology allows, i.e. Michel doesn’t hesitate to crop in on the images with my agreement, it’s something I’ve established with him, i.e. sometimes on the monitor we say: "The final frame will be this", a little more to the left or right, but it’s all in reserve, I always work with a 10% reserve, 10% at the top and bottom, and a little more to the left and right. I use this a lot, and I also do it when we’re in anamorphic. As we avoid dollies for budgetary reasons, but also because we hate dives, or more precisely the optical distortions associated with dives or counter dives, the trick we use in post-production is to move down into the image during the shot, so make a dolly movement using the top reserve, then when the person sits down we move the frame downwards.

CC: Because your frame line is drawn with that extra 10%?

YC: I always have the full reserve and I use the 10% line, I see it all the time, Michel too and also for the left and right. There are always discussions with the sound people, because only very rarely do we let the boom go into the 10% line when it’s very complicated for them and we’re doing fixed wide shots, and then I say, "That’s it, you can go".

CC: As regards this beach, where there are very different states of light, did you choose your shooting times? Did you discuss this with Michel Franco?

YC: I talked about it a lot with the assistant director, because of course there’s the question of chronology, but on this beach I had another problem. When you look out at the sea, the hotel is on the left and on the right is the place we were interested in on the beach, because that’s where the restaurants and bars are, and above all the area where the character is going to go to get tanned, So, with the agreement of the people in the cafés, we moved the café, asking them if they could put their tables a little further away, not just the tables but also the customers, because there’s a mixture of real figuration and false figuration, so a move of about 50 meters gave us 45 to 60 minutes more sun at the end of the day. With the assistant director, while keeping to the chronology as far as possible, we drew up a work plan based on this data. The sun would rise behind the hotel and go down behind the mountain, which wasn’t bad because the character was more or less always in backlight when we were looking at the water, so we made the work plan that way; with Michel again, that’s what’s interesting, if in the morning we were to find ourselves in the situation where I say: the most interesting axis for the light, it’s going to be backlight because it’s morning but if you want to do this scene with the sun in full view we simply have to go the other way.

THE SUN

CC: There’s a moment where the character is sunbathing, and that’s when I realized that you’d chosen your shooting times. It’s quite beautiful how it falls on him, it’s a sun that must be starting to go down.

YC: It was very complicated with Tim Roth, it’s a funny story. In fact, I’d known about it since Chronic, but I hadn’t realized it was going to happen the same way. Tim Roth hates the sun, really hates it, and never goes out in the sun. On Chronic we shot in Los Angeles in the middle of summer, it was terribly hot and Tim refused to get out of the car in the sun, so someone had to be there with an umbrella, not out of coquetry, really because he hates it on his skin. He’s got ginger skin, but in the scenario it’s still someone who’s going to get fried on a beach and decides to speed up his illness, which we don’t know anything about at the time, and who’s going to expose himself to the sun when he shouldn’t be. On Sundown very quickly Tim said he wouldn’t go out in the sun, so Michel and I were shocked. "How come you can tell us that?", so things got tense between Michel and Tim, who were great friends before that. Michel said: "I don’t understand, he’s read the script and now he’s telling me he doesn’t want to be in the sun", and I tried to work things out by suggesting to Michel that, in order for him to have these scenes full of sunlight, he should diffuse the light: I said to Tim: "Well, we need to get the feeling that you’re in full sunlight, but I can help by installing a diffusion, and I also suggested that he could have his head in the shade, if he agreed to have the rest of his body protected by the diffusion. It’s always the same story: on beaches, we have a tendency as operators to go against the light because it’s better for the light, and here in the scenario what was interesting was to go head-on with the sun at our backs, because there was the tough side of this guy who was being grilled on this beach and then meets a girl... All this led to a mixture of shots: at times, for wide shots, I’d go for backlighting, but sometimes, for tight shots like the bird’s-eye shot you mentioned, we’d go for full sun because obviously it was interesting to have him exposed in full sun.

YC : These are ideas for preparation. Michel and I always do a 15-day reading. At the start of our collaboration, we really did 15 days, i.e. two weeks, stopping at weekends, but now we tend to do 7 days in a row, reading the script from top to bottom. I’ve already read it several times, but we reread it together, we stop, we see films, we talk, Michel works a lot by cinematographic references, very few photographic or pictorial or musical references, in fact, it’s really the films, he’s a real encyclopedia.

CC: What were your references for Sundown?

YC: Anything to do with foreigners, they’re all films about loneliness, about lonely people, and how to create that loneliness. The particularity of Sundown is that it’s a character who’s alone in the midst of a lot of people. We both reread the book, to understand why it was similar to the screenplay, because quite naturally, when Michel gave me the screenplay, he told me he’d written it thinking of L’Étranger, without really knowing why, and then I confirmed that it also reminded me of Meursault. In fact, when I reread it, it’s mainly the memories, the moments on the beach, all those memories of him going to the beach, which are only a small part of the book.

He’s a great admirer of Fassbinder, so he’s always trying to find possible references in Fassbinder’s films. For Memory, the Fassbinder film with the woman who falls in love with the handsome Turkish foreigner, I think.

CC: Everyone Else is Called Ali.

YC: Well, Everyone Else is Called Ali. For Memory, it’s a film that Michel said to me: "We have to watch it right away" because of the solitude of this woman and the incongruity of the couple. When we made New Order, Michel made me watch all the Pasolini films again, because there were scenes of political violence. Michel watches a lot of films at the Mexico City Cinematheque, but I’d say that his culture and that of the 1970s and 80s is the Fassbinder, Pasolini and Bergman period.

He’s also a big fan of Woody Allen, but for other reasons, because it’s something inaccessible that he can’t manage to do, and that he’d like to be able to do one day. I’m trying to push Michel to do a comedy because I think he really has potential. He’s already told me several times that he’s started writing, that he just can’t manage it, but I think it would be good if he managed to break out of a line, because now that I’ve made six films with him, there’s a kind of repetition. It’s normal, all authors are like that, i.e. they have their own tricks, but for him, it’s the twists and turns that he manages to exploit very well, the false leads, like in Sundown.

In other words, you believe in a story and in fact it’s not that at all, but something else entirely. He really wants to get out of that mechanism, but like all creators, it’s not so easy to get out of your comfort zone; that’s why we had so much fun on New Order, which was a film about violence. Neither he nor I had ever done anything like that, a kind of detective film with police cars and soldiers. I’d never done that, and Michel hates it, thinks it’s always wrong, so it was fun for us to confront a style that’s out of our comfort zone.

- Read the second part of this interview.

En

En

Fr

Fr