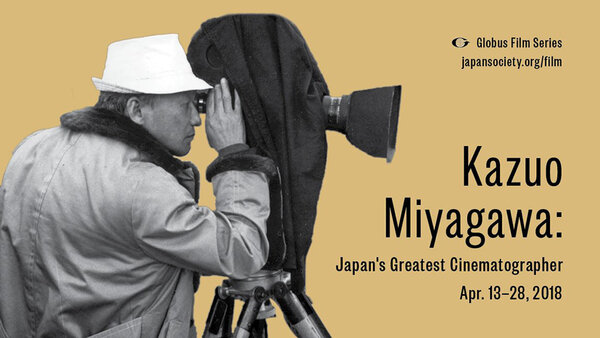

Kazuo Miyagawa (1908 -1999)

By Marc Salomon, consulting member of the AFC“I am a cinematographer. I have never wanted to become a director. A film is not a means of individual expression, but a team effort, a collective undertaking.” (Kazuo Miyagawa)

The films that built Kazuo Miyagawa’s reputation and led him to long being considered Japan’s best cinematographer were mostly from the 1950s : Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, Yasujiro Ozu’s 1959 Floating Weeds, and eight of the eleven of Kenji Mizoguchi’s last films, including Miss Oyu and Street of Shame, without forgetting his equally remarkable work on Kozaburo Yoshima’s River of the Night and Kon Ichikawa’s Conflagration.

Born in Kyoto on 25 February 1908, he was introduced at the age of 12 to the art of Sumi-e, a style of ink wash painting in which the dilution of the ink and the mastery of the brush allows the artist to obtain every possible shade of grey. Miyagawa would later state that “it was my training in ink wash painting that really taught me how to see.” It was also during his high-school years that he began to take photographs for a children’s’ clothing store in his neighbourhood, and then for Nikkatsu Studios in Kyoto. In 1926 (15 May, to be exact !), against his parents’ wishes, who looked down on the world of cinema, he accepted a job in the studios’ lab, where he was trained in developing negatives and toning prints, before joining the camera department three years later : “you had to go through that before becoming an assistant, and you even had to go through a physical aptitude test. [...] Working in the lab taught me the basics, the most fundamental part of making images. When I began making movies, I never used a light meter. I had to gauge the correct exposure by eye. I never used a light meter until Rashomon.”

For a dozen years, Miyagawa worked in different positions (from assistant cameraman to cameraman on the second team, and sometimes even assigned to special effects), first working on popular comedies by Jun Ozaki or Santarō Marune, featuring Ichiro Takazagi or Nosuke Tobayo.

As cameraman on Hiroshi Inagaki’s slapstick comedies, Miyagawa found himself working alongside director of photography Seishi Tanimoto (whose impressive camera movements on Tsuruhiko Tanaka’s 1931 Crimson Bat were recently rediscovered). This helped him develop his own taste and a certain virtuosity in travelling shots and crane movements. He quickly became nicknamed the comedy cameraman ! But he declared that he’d learned as much from those burlesque shootings, on which he always had to come up with an original way of filming, as he did from seeing American films : “In the 1930s and 40s, I admired the work of a few American cinematographers, such as Lee Garmes, Gregg Toland, and William Daniels, and I saw most of their work. I initially thought that Gregg Toland was the best, but later I came to admire James Wong Howe [1] more, doubtlessly because he had an “oriental touch.” His style was closer to Japanese sensibilities, and I came to prefer him over Gregg Toland.”

Still working with Hiroshi Inagaki, Miyagawa became a director of photography in 1943 on Rickshaw Man, produced by the new Daiei Studios, which had just acquired the Nikkatsu Studios, and where he would remain for most of his career. After filming about twenty movies, he met Akira Kurosawa and filmed his first masterpiece, Rashomon, in 1950. “At that time at Daiei, I was more used to filming in a soft style, but Kurosawa wanted more unusual effects on Rashomon, especially in the scenes where Takashi Shimura is walking in the forest and in the “love scene” between Machiko Kyo and Toshiro Mifune. He wanted Mifune to look like the sun, like the Hinomaru (the red sun on the Japanese flag), in strong contrast with the softness of Machiko Kyo. As that required a great deal of contrast between black and white, and not the usual half-tones, I even used mirrors to reflect the sunlight, which I’d never done before.”

At the invitation of producer Masaichi Nagata, with whom he’d already worked in the past, Kenji Mizoguchi left Shochiku and joined Daiei in 1951, whereupon he shot eight films in five years’ time with Kazuo Miyagawa. It is worth mentioning here that before Miyagawa, other very talented cinematographers had worked with Mizoguchi, particularly Minoru Miki, who shot the Japanese master’s seventeen films dating from 1933 to 1947. During that pre-war period, Mizoguchi was fascinated by depth of field and Minoru Miki created very formally-beautiful images in which camera movements, depth of the sets, and chiaroscuro atmosphere were often combined. An example of this is Osaka Elegy (1936) or The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939).

In Cahiers du cinéma n° 158 (1964), script writer Yoda Yoshikata said about Mizoguchi : “He was very interested in William Wyler. The depth of field fascinated him, but because he was sure he could outdo him, he asked Miyagawa to pull off impossible things, such as an enormous depth of field. Despite that, he quickly abandoned that sort of ideas. During the Venice Film Festival, he met Wyler in person. Afterwards, he told me, ‘I won’t be defeated.’ He was that competitive with everyone.” He added, “When Mizoguchi lost his enthusiasm for depth of field, he began to tell stories ‘laterally’, using panoramic or travelling shots. You know that in Japan, there are stories drawn on rolls of paper that are unrolled horizontally. Mizoguchi tried to find the equivalent of that first in the screenplay, and then in the camera work.” In the documentary Kaneto Shindō dedicated to Mizoguchi in 1975, Miyagawa added : “I met him when his legendary ill-humour and aggressiveness had already given way to an extreme softness. For him, a film looked like a rolled-up drawing, in which the successive images told a regularly-progressing story. Once the story was told, it had to procure a feeling of intense satisfaction. He wanted his films to be like that.”

With Mizoguchi, Miyagawa found the right balance within his images, which subtly reconciled formal beauty and camera fluidity, half-tones and chiaroscuro, contrast and definition, realism and dreamlike fantasy, on-location sets and studio sets. He had a bit of James Wong Howe in him in the way he brought light into the frame without any splashy effects, and a part of Gianni Di Venanzo in the way he mastered tonality, which he was able to play with like a musician using all of the notes in the scale. Another comparison could be drawn with Léonce-Henry Burel’s work, in whose opinion the interiors in Japanese films were ‘nearly perfect’.

Unforgettable are the luminous and satiny images of Miss Oyu, the escape of the two lovers into dusky landscapes in The Crucified Lovers, the picnic scene on the banks of Lake Biwa and then Genjuro’s return to his destroyed house where he thought he’d find his wife, who’d died in the meantime in Ugetsu, the wandering of the mother and her two children through grey landscapes that were nonetheless both matte and bright in Sansho the Bailiff, and lastly, of course, the last scene in Street of Shame, one of the most beautiful movie endings ever made. Miyagawa also explored colour with Mizoguchi (Shin Heike Monogatari, in 1955). Until then, he’d only filmed the outdoor shots on Teinosuke Kinugasa’s Gate of Hell, in 1953.

Even though he said he preferred black and white “because most people don’t use colour creatively,” Miyagawa explored a very selective, and almost monochromatic, use of colour with Kozaburo Yoshimura (River of the Night and NightButterflies) and Kon Ichikawa (Her Brother).

It was specifically for Ichikawa that Miyagawa and the Daiei Studios’ lab devised the “bleach bypass” technology in 1960 as a way of desaturating colour. But it was again in a gloomy grey black-and-white with Scope-frozen frames that he filmed Ichikawa’s Conflagration (an adaptation of Yuko Mishima’s novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion). Ichikawa “fragmented the image much more than any other filmmaker. He thought the camera should play an important role in the staging, almost as though it were an actor in its own right. That’s why half of the frame was often filled by a “shoji” (paper screen) or even by darkness.” Miyagawa once again masterfully used the Scope, in 1961, on Kurosawa’s Yojimbo.

In the meantime, in 1959, Yasujiro Ozu had exceptionally decided not to work with Shōchiku studios and his faithful cameraman Yuharu Atsuta and came to Daiei for the shooting of Floating Weeds. Kazuo Miyagawa - used to the meticulously choreographed travelling shots on Mizoguchi’s films and the strong compositions and contrasts on Kurosawa’s - was impressively able to adapt to Ozu’s more static style and razor-precise shots. His work on colour was equally as remarkable, using little discreet touches of colour within a context of dark half-tones.

Although the rest of his career never again reached the same summits, it remained highly diverse as Miyagawa accumulated new experiences and new collaborations. In 1964, he was in charge of the cinematography of the Tokyo Olympic Games, and, in 1966, he collaborated with Russian cinematographer Aleksandr Rybin on Kinugasa’s last film (Malenkiy Beglets). From 1964 onwards, Miyagawa worked on a half-dozen works from the well-known “Zatoichi” series, following the adventures of the eponymous hero, a blind, wandering masseur who is also an expert in “Iaidō” (Japanese martial art of the sword). The visuals of the film were enhanced by a few quick panoramic shots and punch zooms, but which never abandoned a high level of formal rigour (quality of indoor lighting, dusk scenes, misty landscapes, photogenic faces, etc.). Examples include Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold (1964) and Zatoichi and the Fugitives (1968).

In the last part of his career, Miyagawa looped the loop by working on a number of films with Masahiro Shinoda (Silence, in 1971), who was Ozu’s former assistant and an emblematic figure of the Japanese New Wave.

Lastly, Kazuo Miyagawa began preparing and trials for Kurosawa’s Kagemusha, in 1980, but had to drop out of the project for health reasons. He died in Kyoto on 7 August 1999 at the age of 91.

[1] We note in passing that allusively, James Wong Howe was DoP on Martin Ritt’s Outrage, in 1964, which was a remake of Rashomon

En

En Fr

Fr